West Plains residents who turned out for meetings this month hoping to learn more about efforts to fix water contamination that came from the use of firefighting foam on Fairchild Air Force base came away frustrated at what they see as a the lack of information and communication.

Fairchild’s Restoration Advisory Board (RAB) met Wednesday, February 7, followed that evening by an open house. The Restoration Advisory Board includes government and community representatives designed to give stakeholders involvement in the environmental restoration process.

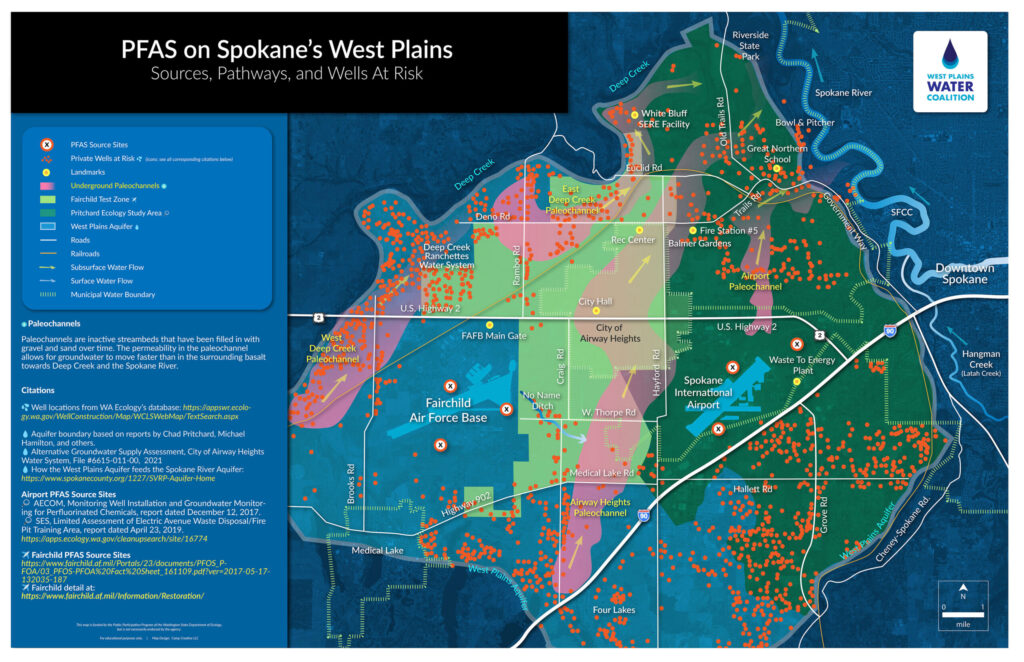

The firefighting foam used at Fairchild from the 1970s to 2016 contained “forever chemicals” known as PFAS. In 2017, Fairchild discovered PFAS contamination in water at the base and the well testing soon spread, revealing contamination in many residential wells as well as wells used in the City of Airway Heights water system.

Since then, the testing has continued. Some families were provided with bottled water to drink and 90 Granular Activated Carbon (GAC) filtration systems were installed in some homes.

The Environmental Protection Agency has set a lifetime drinking water health advisory for PFAS at 70 parts per trillion. Research into the health effects of the chemicals is ongoing, but they are thought to be connected to numerous health problems, including cancer. The level limit set by the State of Washington is 25 ppt, but as a federal entity the Air Force uses the limits set by the EPA.

John Hancock, who sits on the Restoration Advisory Board and is president of the West Plains Water Coalition, said that Fairchild promised transparency with the community years ago but hasn’t delivered it. He hoped new information would be presented to the community this month but the presentation centered around current and future testing. “The RAB meeting was a big helping of nothing,” he said.

During the meeting it was reported that the Air Force has sampled 427 private wells and detected PFAS levels above 70 ppt in 102 wells, including two of four of the wells used by the city of Airway Heights. Another 92 wells had levels of PFAS below 70 ppt.

One well located on the base had levels of 187,000 ppt. Levels found in wells off-base had levels as high as 5,700 ppt.

In 1970’s the United States banned the use of pesticides using the chemical DDT because of concerns over health impacts to animals and humans. Hancock said that the toxicity of DDT was measured in parts per million, making it much less toxic than PFAS. “That’s the potency of what’s still in the ground,” he said. “PFAS is a million times more toxic than DDT.”

Hancock also takes issue with the boundary of the monitoring area established by the Air Force, which sits mostly to the north and east of the base. In many areas, Hancock said, the boundary line seems arbitrary because it is a straight line as if the groundwater just stopped moving there. While some who live outside the boundary area have chosen to have their wells tested, the Air Force will not pay for it. Hancock said that he’s concerned that some people outside the established testing area who cannot afford the $500 test might be drinking contaminated water and not know it.

“They refuse to release the actual data,” he said. “They just ask us to trust their boundary. We keep asking for information they won’t give.”

The government is still in Phase 1 of what is expected to be multiple phases. In addition to water and soil testing, 19 new monitoring wells have been installed on base with four more coming this spring. Seven off-base monitoring wells have already gone in and another nine are scheduled for this spring. Another 10 monitoring wells are expected to be installed inside the Airway Heights city limits.

A FAFB spokeswoman said the contamination is an “ongoing investigation” with no set timeline.

Hancock said a lot of attention has also been spent on soil samples. “There’s no public health acknowledgement for the humans,” he said. “The Air Force just seems concerned about the dirt.”

The RAB meeting was a tightly controlled environment, Hancock said. Only 10 minutes were allocated for questions from the crowd of 200 residents and they were only allowed to ask questions about the data presented at the meeting. “There are a lot of neighbors who went there to talk and no one would listen,” he said.

Residents have many questions, including whether it is safe to eat fruit and garden vegetables grown in the contaminated area, Hancock said. Others want to know if it is safe to raise cattle and other livestock.

Jerry Goertz is president of the Deep Creek Ranchettes Water Association in the Deep Creek neighborhood about two miles north of Fairchild. He attended the recent RAB meeting and said it appears that little has changed since the contamination was first discovered. “They have a narrative they’re pushing out and how it gets presented,” he said. “I know this takes time, but it seems like the contamination on base is being speed tracked for cleanup and outside the base it’s going to be years before anything gets done.”

He said he heard Hancock push for more public comment time and be turned down. Goertz said residents were told they could submit their questions online, which he did. “We’ll see if they respond,” he said. “It’s frustrating for lots of people.”

Goertz said his water system has been tested for PFAS regularly since the contamination was discovered and so far, none has been found. While relieved about the test results, Goertz said he worries it might change in the future. “We’re living on borrowed time out there,” he said. “Something could change. We’re so close to the area, we could end up contaminated. We don’t know, so we have to continue to test.”

Goertz said he recently learned that the West Prairie Village Mobile Home Park on Craig Road, which is inside the monitoring area, tested positive for PFAS. “They just found out they’re contaminated, but it’s not over 70 ppt,” he said. “Fairchild won’t do anything for them.”

Hancock said he was told it might be 40 years before his water is clean again. He, like many others, is frustrated that there is no timeline for restoration nor any indication of what restoration will entail.

Lawsuits have also been filed in regards to the contamination. A group of residents have sued the United States, the Department of Defense and the U.S. Air Force. The residents included in the lawsuit include one who was forced to sell his property at a loss after the contamination became known and a married couple who used to sell crops from their farm that was irrigated with contaminated groundwater.

The Kalispel Tribe of Indians and Northern Quest Casino have also sued the U.S. government and several firefighting foam manufacturers.