The West Plains Water Coalition continued its mission to educate West Plains residents on the issues surrounding the forever chemicals known as PFAS that have been found contaminating many wells in the area by hosting a public meeting featuring the co-director of PFAS Project Lab, a national effort to study and track PFAS contamination.

Alissa Cordner is an associate professor of sociology at Whitman College in Walla Walla, teaching classes on environmental sociology and environmental health. The PFAS Project Lab she helps direct is affiliated with the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute at Northeastern University.

Cordner said she’s been studying PFAS for 10 years. “We know a lot more than we did 10 years ago, but there are a lot of questions to be asked and answered,” she said.

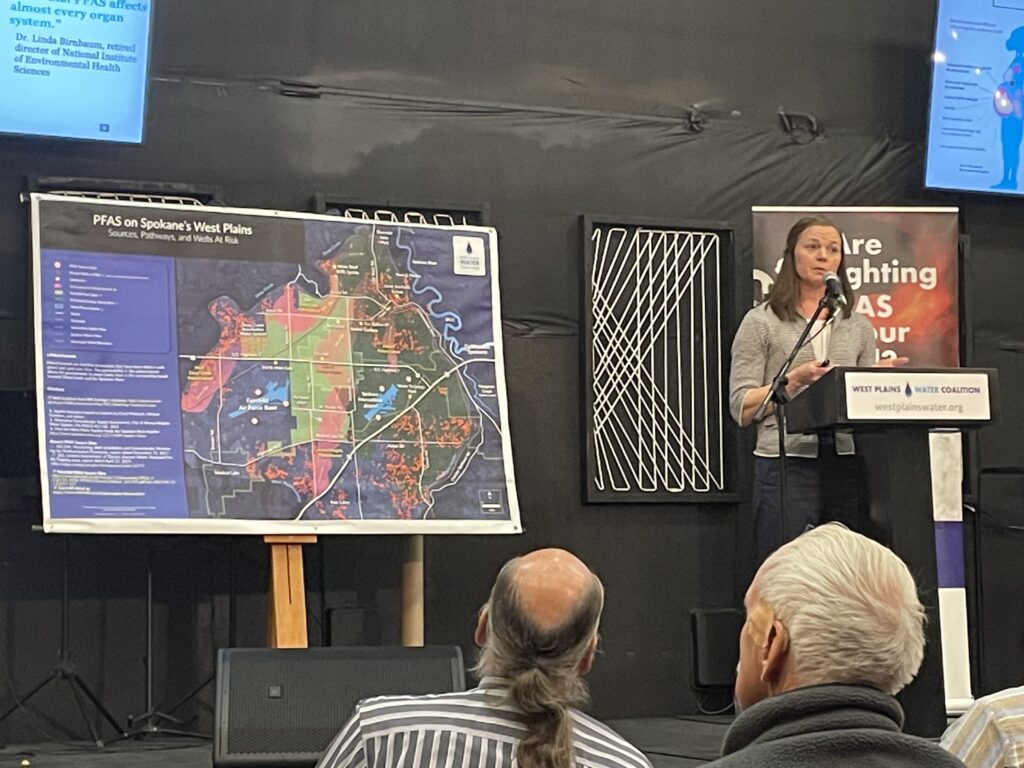

PFAS chemicals, which can linger in the environment for decades, were an ingredient used in firefighting foam used at airports for decades, including at Fairchild Air Force Base and the Spokane International Airport. In recent years water contamination has been discovered in the West Plains and studies are underway to determine how far the contamination has spread and how to clean it up. It’s a multi-pronged effort, with the Department of Defense overseeing cleanup of the contamination close to Fairchild and the Washington State Department of Ecology overseeing cleanup outside the DOD study boundaries.

It’s thought that exposure to high levels of PFAS leads to higher rates of thyroid issues, kidney problems, high cholesterol and some forms of cancer, but research is still underway.

Cordner said one of the goals of PFAS Project Lab is to make newly discovered scientific data accessible and useful. “PFAS are a complicated set of chemicals,” she said.

The Project Lab started tracking known PFAS contamination sites in 2016, when there were only a dozen known sites. “We now have more than 2,000,” she said.

Firefighting foam is not the only source of PFAS contamination. The chemical is used in many products, including cookware, and can contaminate factories and industrial sites. PFAS waste sites, including incinerators, can also cause contamination. Taking all of that into account, there could be as many as 57,000 contaminated sites across the country, Cordner said. Testing has not been widespread and there’s just no way of knowing how many are actually contaminated, she said.

“This is in the absence of high quality testing,” she said. “We know there are contamination sources out there that have not yet been identified.”

The Federal drinking water limits for PFOA and PFOS, two of the most common PFAS chemicals, were set at 4 parts per trillion in April. The limits for PFNA, PFHxS and HFPO-DA (GenX) is 10 parts per trillion. A well on Fairchild Air Force Base has tested at 176,200 ppt and the private well outside the base boundaries that tested the highest had 4,400 ppt of the chemicals.

“The contamination at Fairchild is indeed one of the highest we’ve seen around the nation,” she said.

Several dozen people came to hear Cordner speak and almost all of them indicated that they had tested their well water for PFAS. Only five of those in attendance had their water test clean.

Residents had a chance to ask questions, and the common question of whether produce or animal products produced in areas with contaminated water were safe to eat. Cordner said there has not been enough research done to know, though PFAS have been found in eggs and meat. It is thought that some plants retain PFAS while others do not. It also depends on whether contamination exists just in the water or also in the soil, Cordner said.

The Washington State Department of Health has been studying levels of contamination found in beef, chicken, turkeys and chicken eggs. A small sampling of 11 households earlier this year showed that when animals drink contaminated water, the PFAS can be found in their meat and eggs.

Though the study was small, it appears to show that there are some things residents can do to mitigate contamination. Two households with nearly identical levels of contamination were studied and both raised chickens for their eggs. In the home where chickens were given contaminated water and scratched in the dirt, the level of PFAS in the eggs was so high the family was told not to eat them. But in the home where the chickens were given filtered water and kept in a coop with a thick layer of pine shavings to prevent access to the dirt, the level of PFAS contamination in the eggs were very low.

That study has since been expanded, though the results of new testing are not yet complete. The Department of Health recently collected meat and egg samples from an additional 37 homes with PFAS contamination in their water.

The recent elections could have a significant impact on the effort to clean up the PFAS contamination going forward, Cordner said. She said she believes Washington State will continue to push to enforce PFAS limits and work toward cleanup of contaminated sites. “I think Washington is a real leader,” she said.

However, Cordner said the election of Donald Trump as president has led to uncertainty about federal PFAS mitigation efforts. She noted that during his first presidential term, nothing was done about PFAS contamination and Trump worked to dismiss many regulations, including those placing limits on chemical contaminants.

“We should expect this overall deregulatory outlook,” she said.

Trump has already announced that he intends to nominate former New York Representative Lee Zeldin as the head of the Environmental Protection Agency. Cordner said that there are PFAS contaminated sites in Zeldin’s former district. “He is PFAS aware,” she said. “During his time, he voted yes on three out of four PFAS bills.”

However, Zeldin has spoken in favor of deregulation in general and voted against new regulations on other chemicals, she said.

Corner said she would not be surprised if the Trump administration reverses the new PFAS drinking water limits as well as a recent DOD decision to treat some PFAS contaminated sites as Superfund sites. “I personally would not be surprised if they revisit those federal levels,” she said.

More information at the PFAS Project Lab and the data it has been collecting can be found online at https://pfasproject.com.