We often take for granted that which we cannot always see.

Take water, for instance. It’s the stuff of life, as the saying goes, and not just individual life but the life of whole communities.

We don’t know how important that stuff is until it’s taken away, a fact many Airway Heights and rural West Plains residents learned in 2017, when the water they were using was discovered to be contaminated by decades of use by Fairchild Air Force Base — and more recently Spokane International Airport — of man-made chemicals that can lead to cancer and other diseases.

The result of the contamination included closing of private and municipal wells, distribution of bottled water until new sources could be found, and possible links to the deaths of several residents.

It also created a greater urgency to understand the properties of the water beneath our feet, and how the system that conveyed that water — the West Plains Aquifer — really works.

Giant floods of hot lava

The West Plains Aquifer’s origins begin several hundred miles to the southeast near the borders of Washington and Oregon states. According to the United States Geological Service, between 16.7 million – 5.5 million years ago, a series of generally north-northwest aligned linear fissures in the earth began disgorging cubic miles of lava from a subsurface volcanic “hot spot.”

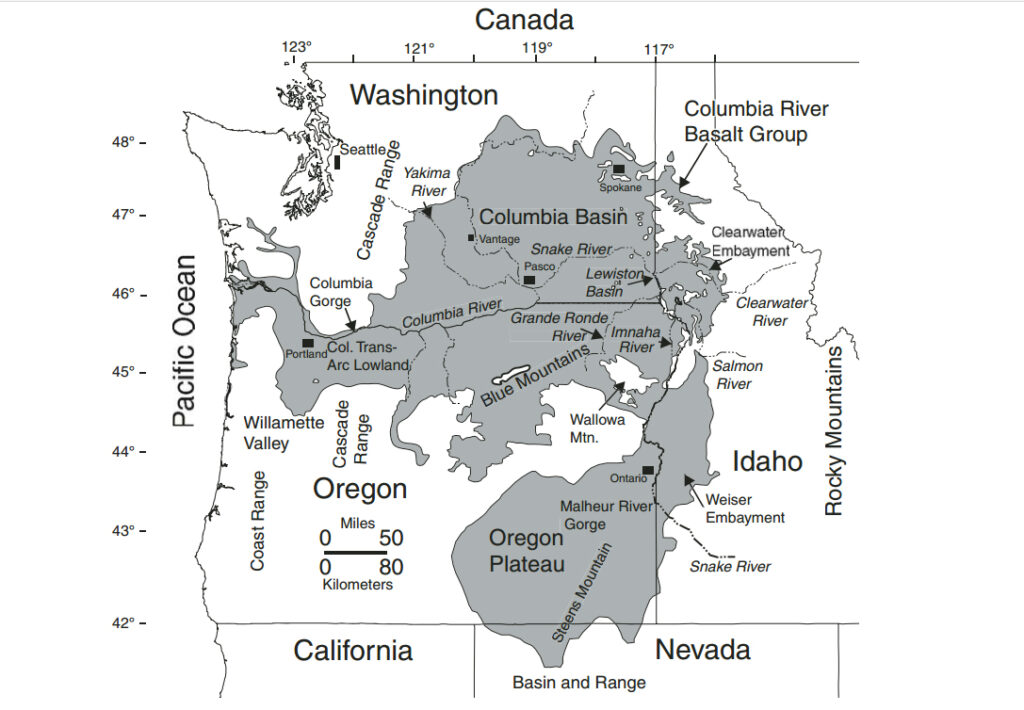

As the North American Plate moved westward, that hot spot moved east and is now believed to be under Yellowstone in northeast Wyoming — but not before vomiting up over 210,000 square kilometers — 81,081 square miles — of lava covering present day eastern Washington and Oregon, some of western Idaho, part of northern Nevada and as far west as the Willamette Valley, eventually reaching the Pacific Ocean.

About 93% of the lava floods erupted between 16.7 million – 15.6 million years ago. As they cooled, they formed stratified, columnar formations known as basalt, with sediment layers of different materials from sand to clay deposited between the different flows over time.

Eventually, seven of these flows created formations collectively called the Columbia River Basalt Group (CRBG): Steens Basalt, Imnaha Basalt, Grande Ronde Basalt, Picture Gorge Basalt, Prineville Basalt, Wanapum Basalt and Saddle Mountain Basalt. The formations also contain a number of member flows, such as the Wapshilla Ridge Member in the Grande Ronde and the Sentinel Bluffs Member in the Wanapum.

“The formations, members and many flows of the CRBG can be identified by looking at and measuring the rocks’ chemical composition, physical characteristics, magnetic polarity and by observing the position of lava flows in relation to each other,” according to the USGS’s Cascade Volcano Observatory.

The largest of these formations is the Grande Ronde (16.2 million years ago) and the Wanapum (16 million years ago) at 35,747 and 2,920 cubic miles respectively. Both formations extended north through the West Plains and past the current location of the Spokane River, flowing around pre-Miocene, erosion resistant bedrock hills known as “steptoes” located on a line east and west of Four Lakes.

According to research by Eastern Washington University Geoscience Department students to be presented at a Geological Society of America conference in Spokane this May, these buttes were likely created hundreds of millions of years ago, and are a result of “Cretaceous fold and thrust deformation as well as Eocene uplift.” The result is that, while groundwater contained within the CRBG basalts typically follows the basalt formation flows to the center of the Columbia Basin, according to a 2019 report by researchers at EWU, Washington State University and Spokane County Water Resources, water in the Grande Ronde and Wanapum formations on the West Plains flows to the north/northeast towards the Spokane River.

“With these hills, we’re in a unique position,” Geoscience Department professor Dr. Chad Pritchard said.

Giant floods of cold water

Over time, natural processes created several north/northeast oriented ravines — paleochannels — in the West Plains basalt, with water filtering into the underground rock layers to create an aquifer. This process was also helped during the last Ice Age with the formation of Glacial Lake Columbia, which covered part of the West Plains north of Airway Heights.

But about 17,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, that changed in a dramatic way. According to the Glacial Lake Missoula website, a finger of ice from the Cordilleran Ice Sheet — a lobe — extended into a narrow portion of land near modern Lake Pend Oreille called “The Purcell Trench.”

The lobe created a 2,500-foot tall ice dam in today’s Clark River Drainage, backing the water up to the east and creating Glacial Lake Missoula — a lake containing as much water as today’s Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined. Eventually, water pressure shattered the ice dam, releasing a torrential flood that flowed at 386 million cubic feet per second, 30 –50 miles per hour down the Trench, into the Spokane River Valley and out over the West Plains and beyond, eventually reaching the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of the Columbia River.

On the West Plains, some of the water gushed to the southwest towards the Snake-Columbia rivers confluence, carving out the Cheney-Palouse Channeled Scablands. Another river cascaded west along the Spokane and Columbia rivers valleys and eventually emptied into Glacial Lake Columbia.

Between 17,000 and 14,500 years ago, this ice dam formed, broke and reformed, leading to several large floods inundating the region. On the West Plains, these floods deepened the existing paleochannels and filled them with sediment materials, with more sediment covering the area once the floods ceased as the ice sheets retreated north.

With the departure of the ice sheets, the West Plains Aquifer lost it’s biggest and most important recharge source — Glacial Lake Columbia.

Drinking Ice Age water

Lack of a reliable recharge source has made the West Plains Aquifer an isolated, fragile system whose pieces scientists know, but whose interactions are still being discovered and understood. Besides the general lateral movement northward, water also flows vertically and laterally between layers via fractures between the basalt columns.

There is also interaction with the numerous lakes, creeks and wetlands in the area, although scientists and researchers are trying to understand how this works.

“Nobody knows how these lakes and other surface water bodies are connected,” EWU’s Pritchard said.

Most of the wells on the West Plains draw water from the Grande Ronde layer — the largest, deepest and most confined of the two basalt flows. Many of these wells go down hundreds of feet, and in some cases well over 1,000 feet.

Other wells draw from the shallower Wanapum layer, along with pockets of sand-rich portions of sedimentary interbeds in the Latah Formation — a meters thick layer between the two basalt flows. Then there are the paleochannels, which depending upon their fill materials, can either easily pass water through or impede it and appear to be recharged by runoff from the Four Lakes steptoes.

Research indicates there are at least five paleochannels, the largest being the Airway Heights Channel at almost 12 miles long, nearly 2 miles wide and about a half mile deep.

“There’s several smaller ones too,” Pritchard said. “We don’t have enough details, but there’s probably more.”

Depleting and contaminating Ice Age water

Researchers have carbon-14 dated water from a number of West Plains wells. According to the 2019 study, these ages range from 790 to over 10,000 years old, with the ages rising the deeper the well is.

With most of the potable water on the West Plains coming from the deeper Grande Ronde wells, the concern is water is being taken out faster than it is coming in. It’s a term some refer to as “groundwater mining,” and it has significant ramifications for life on the West Plains.

“That is the super scary part of this story,” Pritchard said. “We are slurping up on Pleistocene slushy and the slushy machine broke about 16,000 years ago when Glacial Lake Columbia broke free and stopped recharging the basalt aquifers.”

Adding to the water depletion is an ever growing population on the West Plains that is bringing with it contamination of what water there is. Over the years, that contamination has come from leaking septic systems, construction sites and manufacturing businesses.

In 2017, contamination rose to a new level when polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS, were discovered in private wells around Fairchild Air Force Base and Airway Heights municipal wells. Known as “forever chemicals” because of their slow environmental degradation, perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFOA) and perfluorosulfonates (PFOS) “were key ingredients in a firefighting foam, as well as Teflon, Scotchgard and other consumer chemicals,” according to a presentation by Pritchard.

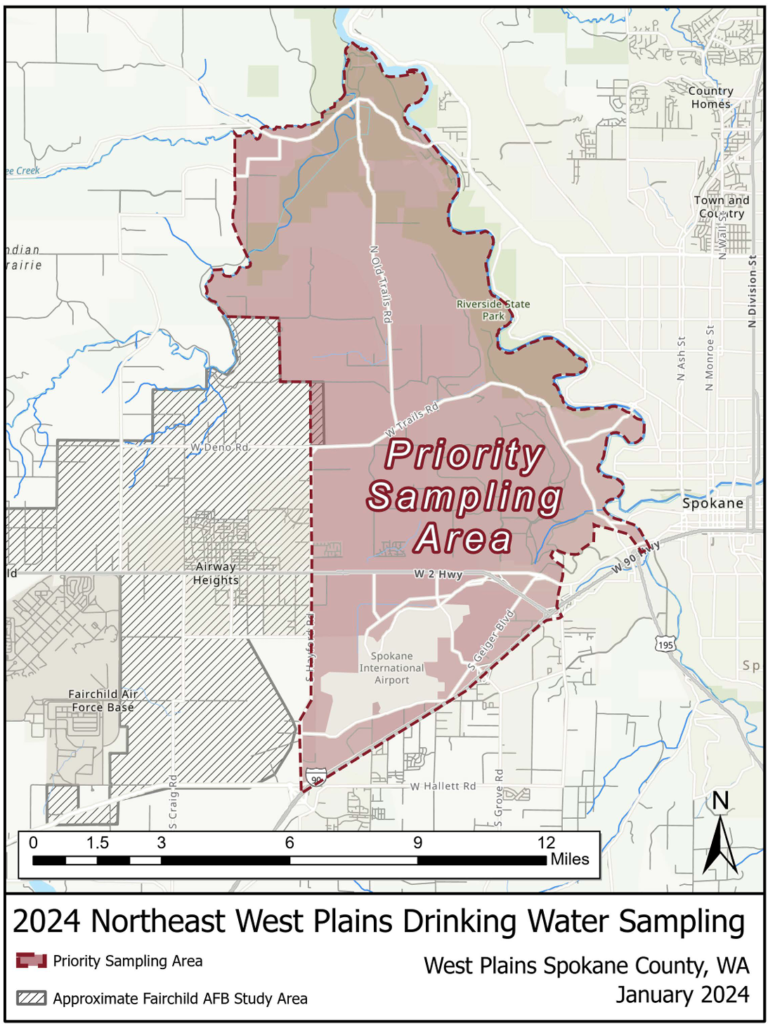

These chemicals have been linked to a number of health defects, “including high cholesterol, immune system and thyroid disorders and certain types of cancers.” PFOS and PFOA contamination was subsequently found in wells in the Palisades area east and northeast of Airway Heights, north of Interstate 90 all the way to the Spokane River.

Contamination levels ranged from single digits in some wells to over 500 parts per trillion (ppt) in others. One part per trillion is equivalent to a single drop of water in a container the size of 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

As to what level of PFAS is considered “safe,” that varies according to the type of chemical. Bri Brinkman, Department of Ecology technical adviser to the EWU’s water study, said originally in 2017, officials combined levels of PFOA and PFOS into one that indicated anything above 70 parts per trillion was considered hazardous — a level currently used by FAFB.

“They rescinded that last year because it was felt it was not protective of human health,” Brinkman said.

Federal agencies are still working on producing safety levels for the different types of PFAS. In 2021, the Washington State Board of Health developed “State Action Levels (SALs)” for five PFAS with 10 ppt recommended for PFOAs and 15 ppt for PFOS.

A SAL is a level that is set to protect human health and is based on the best available science at the time.

Studying chemicals and groundwater

In spring 2023, Pritchard and EWU’s Geosciences Department was awarded a $450,000 state Department of Ecology grant to study the West Plains contamination and how groundwater moves through the region. The two-year study, administered by the city of Medical Lake, looks to eventually produce a three-dimensional model of the West Plains Aquifer that can be used to determine how water flows through the system and potentially reveal other PFAS sources.

“It gives us a deeper understanding of what is layered,” Brinkman said. “It will help identify the flow paths and how PFAS’s move.”

Pritchard said the study will “identify the orientation of rock types that control groundwater flow.” Thirty locations will be sampled four times over the coming year for such conditions as temperature, acidity and the presence of contaminants such as PFAS.

“The study is measuring for 60 types (of PFAS),” Pritchard said. “There are over 2,000 types, made for different purposes and reasons.”

Besides residential and municipal wells, other locations to be sampled include Medical and Willow lakes, Deep Creek, Indian Canyon Creek, the Spokane River, several wetlands, the rain gauge at the NOAA facility on Rambo Road and the Medical Lake wastewater reclamation facility.

“The goal is to mimic reality to some respect,” Pritchard added. “This will be the most extensive study of the West Plains Aquifer to date.”

These samples will be conducted spring through fall 2024. From August – early September, another 150 wells across the area will be sampled. Pritchard and Brinkman also hope private well owners who have had their wells sampled near Fairchild and some of the 308 sampled by the Environmental Protection Agency in the Palisades area will share their data for the study.

Once collected and analyzed, the data will be sent this fall to an environmental statistician at Rutgers University where it will be formatted, calibrated and turned into the 3D model, which will hopefully be available online in time for a final report on the project in June, 2025. “Hopefully this will show us where the water is moving to and how fast it’s moving,” Pritchard said.